Siracusa's Artistic Heritage

Can art exist without belief? In Siracusa, Sicily, the enduring relationship between art and belief has been eloquently expressed through centuries of faith-infused creations, starting as early as 300 AD. Discover how deeply faith permeates the artistic veins of this historic city.

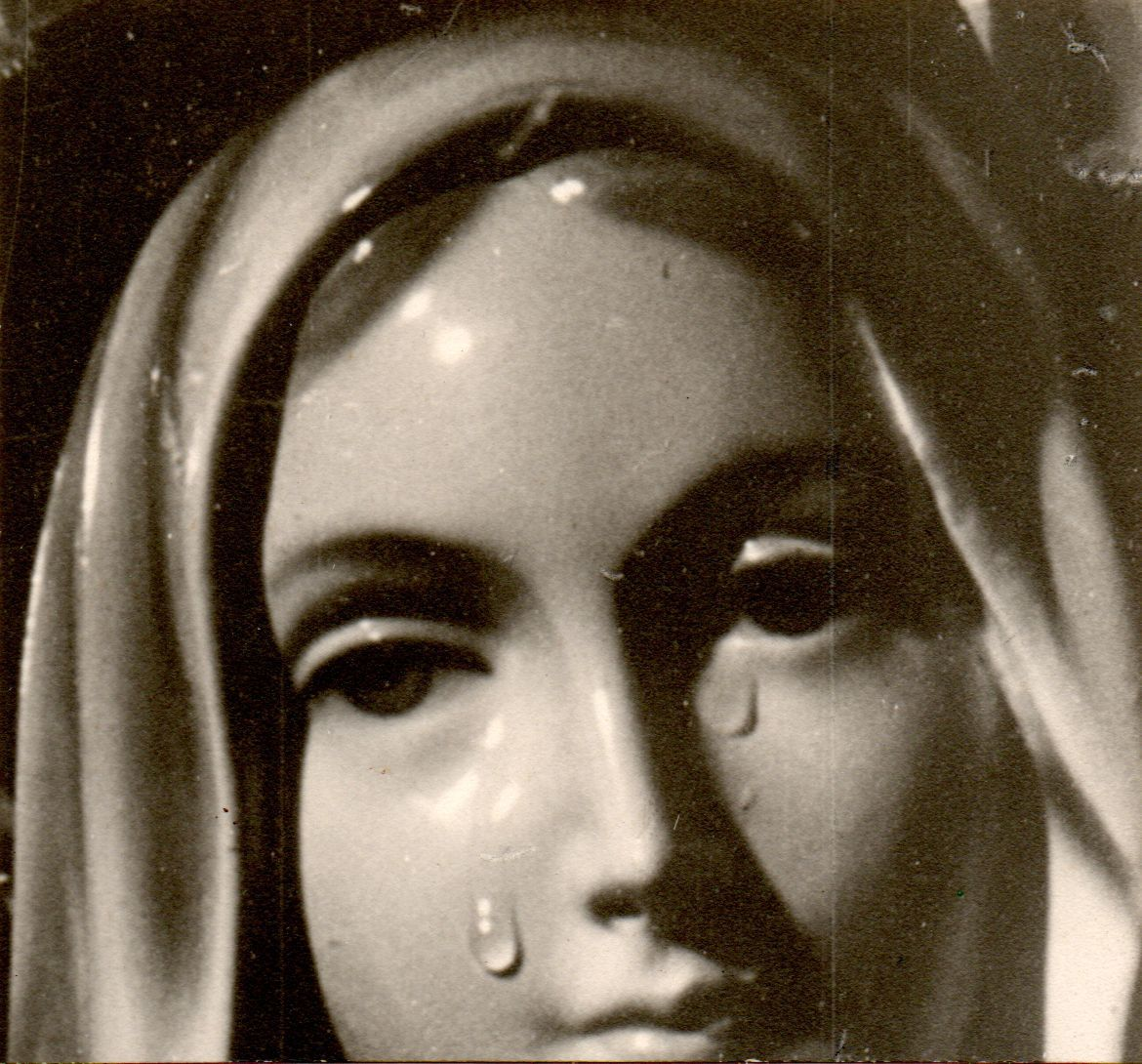

Madonna delle Lacrime, Aleteia

We all know the drill. Family vacation: cultural tours, lots of religious museums, and churches. You stroll around with no clear direction. The information transcends you; you see it, you understand it, but you can’t grasp it. It’s an intangible idea. Is there a way to feel this art on your skin? To absorb every bit and piece of sentiment into your being?

In Sicily, religious art does not stand on its own as an isolated piece of cultural heritage. It is and has been fueled by belief for centuries, constantly and miraculously giving back the chance to believe. Faith creates art, and art generates faith.

Siracusa Protector Saint Lucy (Santa Lucia) is one of the biggest sources of belief in the city. As a Roman Christian martyr, Santa Lucia died during the Diocletianic Persecution in 304 AD. As a follow-up from this event, the veneration of Santa Lucia began to be present in the Siracusan culture as early as the sixth century, also featuring in ancient Roman Martyrology.

The martyr’s sacred role for the city of Siracusa also became the subject of prestigious artistic expression centuries later, with Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Seppellimento di Santa Lucia, dated 1608.

Seppellimento di Santa Lucia (1608), Michelangelo Merisi di Caravaggio. Arte.it

As a fugitive from the prison of Malta, Caravaggio fled to Siracusa in 1608, where the Senate commissioned the artist with a painting for the redevelopment of the Church of Santa Lucia. The painting was then placed in the Church’s altar on the 13th of December 1608, the day when Patrona Santa Lucia is celebrated - up to this day.

Caravaggio’s Seppellimento di Santa Lucia demonstrates the power of faith and religious commitment in nourishing artistic genius and progress. Caravaggio does not represent the usual: instead of showcasing Lucia’s sufferable death, he shows us the moment she is laid to rest peacefully. The bishop’s arm extends to bless Lucia’s body - the same hand gesture Jesus acquires in La Vocazione di San Matteo (1599-1600). Caravaggio’s painting speaks clearly: he does not aim at portraying torture, but rather, death. The protagonist of the painting is the immense pain of eternal death - a death that symbolizes Santa Lucia’s role as a martyr - as opposed to “glorious,” volatile and temporary torture.

More than a century after Caravaggio’s art, the Siracusans' faith in the protective powers of Santa Lucia renewed itself through art once again, this time sensationally. In May 1735, the city of Siracusa was under Austrian rule and undergoing major hardships in fighting off the incoming Spanish siege. As the population grew exponentially desperate and the chances of victory against the opposing forces thinned, they prayed to Siracusa’s Santa Protettrice, Lucia. During those days, the sculpture of the dying Santa Lucia, made by Tuscan sculptor Gregorio Tedeschi a century earlier, miraculously shared her solidarity with Syracuse’s population during those hard times, shedding drops of sweat from her forehead, hands, and feet. The sweat was proclaimed ‘real and miraculous’ (“vero, reale e miracoloso”) on January 20, 1736, by Siracusa’s Curia.

Scultura di Santa Lucia Morente (1634), Gregorio Tedeschi.

While this event strengthened the solidarity to a religious belief already communally grounded in Sicilian culture, it also implies a dichotomous and two-way relationship between art and religion. For one, this event inspired further art: it became the beginning of a historical parenthesis where Florentine sculpture brought the Renaissance to Sicily - with important artists working in Palermo and Siracusa, including Tedeschi himself. But the miraculous sweating of Santa Lucia’s statue underlines one further layer of significance: just as prominent artists such as Caravaggio used religion as a source of inspiration for their art, faith expressed itself through art, even generating more art. In a way, the statue became a proper vehicle for religious beliefs to bloom and assert themselves as real and tangible entities in the power of artistic expression.

This was not the last time art actively spoke of faith in Siracusa. In August 1953, Antonina Iannuso suffered epileptic fits and severe pains during her pregnancy. On August 29, she discovered that the plaster statue of the Madonna above her bed was shedding tears. On September 1, a commission of doctors and analysts took up a sample of the liquid that flowed from the eyes: ‘they are human tears,’ states microscopic analysis.

Thousands of people gathered around the house of the Iannuso following the miracle.

The popular response to this event was immense: children struck by illness were extraordinarily cured following their visit to the Iannuso home, and the subsequent religious frenzy arising from this once again served for further artistic developments in the upcoming years. In October 1954, Pope Pius XII approved of the weeping Bust of Our Lady of Syracuse, which was later moved to the newly consecrated Crypt (Santuario della Madonna delle Lacrime) in 1968. The combination of these occurrences inspired a major architectural bloom in Siracusa, which saw the affluence of international architects and artists to build the Crypt’s Shrine, later developed by French architect Michel Andrault.

While there is tons of room for skepticism around the proofs and circumstances of the abovementioned occurrences - in terms of the authenticity of the miracles described - these events nevertheless exhibit important peculiarities in the ways we, as human beings, respond to artistic input when it comes to belief.

The interrelation between the distinct fields of art and religion is no new discovery - art often speaks of religion, and it did so for centuries up until today. When I look at Siracusa, however, my definition of sacred art changes: it is not solely about the content, but it is all about expression, about what it quite literally and tangibly speaks of. While miracles often take on the role of giving hope to the people, here they give a voice to art. Santa Lucia’s sweat and the Madonna's tears mobilized communal hope and strengthened religious belief to the point in which the artistic and architectural advances that followed would have scarcely been possible without them. Could art exist without faith?