Meet Ulya Soley

Meet Ulya Soley, a curator renowned for her thoughtful integration of psychological insights and art historical knowledge into the craft of curatorial practice. Her exhibitions are celebrated for their intellectual depth and ability to engage viewers with provocative questions about identity and history through the lens of contemporary art. Ulya’s work is characterized by a thorough exploration of cultural narratives, challenging traditional exhibition formats and encouraging meaningful dialogues between the artwork and its audience. In her practice, Ulya uses a research-driven strategy that carefully recontextualizes complex themes within the art world, leading to exhibitions that stimulate intellectual engagement and emotional responses. Her projects delve into the detailed connections of historical insights and contemporary issues, designed to initiate discussions that resonate both within and outside gallery spaces.

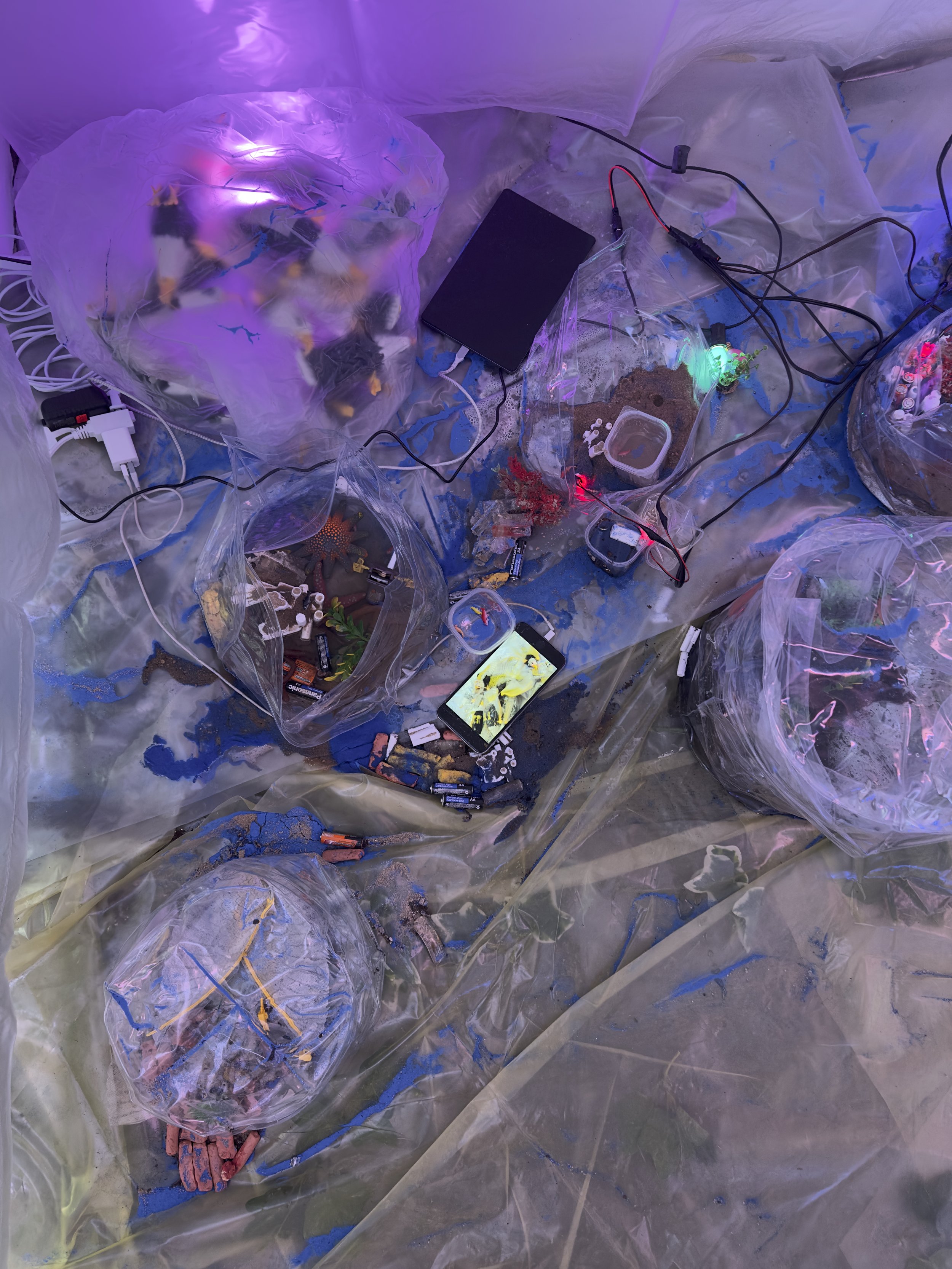

Spirits on the Ground: Kerem Ozan Bayraktar, installation view, DIANA New York. Courtesy of the artist and SANATORIUM. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Could you detail your trajectory from art history and psychology studies to your distinguished role as a curator? How have these disciplines been integrated in your approach to curatorial practices?

My academic background in both social sciences—particularly psychology—and art history has played a significant role in shaping my curatorial approach. Studying psychology provided me with a strong foundation in research methodologies, analytical thinking, and an understanding of how people engage with narratives, environments, and visual culture. While I don’t necessarily focus on psychology as a subject in my curatorial work, its methodologies and ways of thinking have been integral to my approach. The discipline trained me to ask critical questions, assess patterns, and consider different layers of meaning, all of which have influenced my research-oriented curatorial practice.

Art history, on the other hand, was instrumental in paving my way into the curatorial field. At McGill, I studied not only the history of art but also contemporary art theory, with a particular focus on post-World War II art. The program was rigorous, demanding both critical engagement with historical contexts and an awareness of contemporary discourses. My time in Montreal was formative—not just academically, but also in terms of exposure to museums, galleries, and artist-run spaces. Having direct access to such a vibrant art ecosystem expanded my understanding of the curator’s role beyond exhibition-making. I became increasingly interested in curating as a practice that extends into research, writing, and public engagement.

These two disciplines continue to intersect in my work. My research-driven approach is informed by my background in psychology, while my art historical training provides a strong foundation for engaging with artistic practices and exhibition-making. Together, they allow me to think critically about how exhibitions communicate ideas, how audiences experience them, and how curatorial narratives can create meaningful dialogues between artworks and viewers.

Your interest in using a queer feminist lens to explore future scenarios is stimulating. Could you elaborate on how this ideological framework informs the selection and interpretation of artworks and exhibitions? Additionally, could you discuss how this perspective was applied in a project that challenged traditional narratives and activated dialogue among its viewers?

For me, queering curatorial practice is not only about collaborating with queer artists but also about embracing methodologies that challenge normative structures—whether in art, politics, or institutional frameworks. It involves a critical and fluid approach that disrupts conventional modes of exhibition-making, opening up alternative ways of engaging with artworks and audiences. This could mean rethinking spatial configurations, challenging institutional protocols, or introducing new modes of interaction that subvert expectations. For example, it might involve changing the usual entrance of an exhibition space to disrupt habitual movement patterns or encouraging an institution to reconsider its standard operational rules to accommodate more inclusive and experimental practices.

One project where I actively applied this perspective was Souvenirs of the Future, a group exhibition that challenged traditional ways of engaging with a historical collection. The show brought contemporary artists into dialogue with a craft collection spanning from the 18th to the 20th century, inviting them to create new works that were not merely reflective but critically provocative. Rather than treating the collection as an archive of fixed meanings, the artists activated it as a space of speculation and reinvention. This approach disrupted the typical reverence given to historical objects, positioning them instead as sites of inquiry and intervention.

The exhibition invited viewers to reconsider their relationship with historical narratives and material culture. It also highlighted how contemporary artistic practices can offer speculative futures rather than static interpretations, reinforcing the idea that queerness is not just an identity but also a methodology—a way of thinking that resists fixed meanings and embraces fluid, evolving possibilities.

Souvenirs of the Future, exhibition view. Courtesy of Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation, Pera Museum. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Speculative thinking is central to your methodology. Could you discuss how this approach challenges conventional narratives within your curatorial projects, particularly those that address the interplay between nature and societal constructs?

Speculative thinking emerges from the necessity of envisioning alternatives, especially in a world where existing systems continue to reinforce discrimination, environmental collapse, and political failure. The persistence of patriarchal structures, the dominance of capitalist relations in shaping governance, and the alarming global rise of the far right all indicate that conventional models are failing us. In this landscape, speculation is not simply an exercise in imagination—it becomes a critical tool for reconfiguring the way we think about the present and its possible futures.

Within my curatorial projects, speculative thinking often manifests in the interplay between nature and societal constructs, particularly in how we perceive and represent systems, non-human agencies, and post-human futures. Rather than approaching nature as a static backdrop to human activity, I am interested in exhibitions that challenge anthropocentric narratives and explore more entangled, symbiotic relationships. This means working with artists who propose alternative ontologies—where the boundaries between nature, technology, and culture are blurred, and where speculative fiction, mythology, and scientific inquiry coexist.

Speculation allows for a radical departure from the given, offering an imaginative space where new social and political possibilities can be tested. In this sense, my curatorial methodology is not only about presenting alternative futures but also about destabilizing fixed perspectives in the present. I aim to work on projects that function as laboratories for reimagining the present—not as it is, but as it could be.

Balancing roles across different platforms, from Pera Museum to independent curatorial projects, presents unique challenges and opportunities. How do you navigate these varied spaces in terms of curatorial expression and thematic exploration?

I’ve been working at Pera Museum since 2013, and over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to engage with various aspects of exhibition-making, from research and conceptual development to production, publications, and public programming. This experience has provided me with a comprehensive understanding of how different departments within an institution operate and collaborate to bring exhibitions to life. My institutional role has enabled me to contribute to large-scale, ambitious projects such as A Question of Taste and Souvenirs of the Future, both of which explored compelling themes with broad audience engagement.

One of the most rewarding aspects of institutional projects is their ability to reach a wide public. It’s exciting to shape a curatorial narrative that can resonate with diverse audiences and create meaningful connections. At the same time, independent curatorial projects provide a different kind of space—one that is often more flexible and allows for experimentation. Without the structural constraints of an institution, I have the freedom to explore unconventional formats, challenge established exhibition methodologies, and engage more directly with artists in ways that might not always be possible within an institutional framework.

I see these two modes of working as deeply interconnected. The structured environment of an institution offers resources and stability, while independent projects push me to think critically and explore new approaches. Each context informs the other, and this dynamic exchange is something I find incredibly enriching. It allows me to continuously refine my practice while adapting to different platforms and audiences.

A Question of Taste, installation view. Courtesy of Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation, Pera Museum. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

The incorporation of experimental writing and fiction in your curatorial texts adds a unique narrative depth. How do these elements function to deepen thematic engagement and viewer interaction within your exhibitions?

I’m interested in experimenting with writing, particularly in how fiction and poetry can expand the curatorial narrative beyond conventional explanatory texts. Writing allows me to explore different registers of engagement, offering an alternative way for audiences to connect with the works on display. Rather than relying solely on didactic texts that frame the artworks in analytical or historical terms, fiction introduces an affectionate and interpretative dimension, creating space for multiple readings and personal associations.

For instance, in Burak Ata’s solo exhibition Light the Fire, Drink the Sea, I wrote short stories for each chapter of the exhibition. These texts did not function as direct descriptions of the works but rather as parallel narratives that resonated with their themes. By integrating storytelling, I sought to evoke moods, sensations, and speculative scenarios that extended the exhibition’s conceptual framework, allowing audiences to experience the works through a more poetic lens.

Light the Fire, Drink the Sea: Burak Ata, exhibition view, Martch Art Project. Photo: Cemil Batur Gökçeer. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Another project that incorporated experimental writing was Magazine 15, a zine I edited where I commissioned artists to produce visual works inspired by Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous. In response to each artwork, I wrote flash fiction pieces, creating a layered conversation between text and image. This process not only deepened the connection between the literary and the visual but also encouraged a more open-ended mode of engagement—one where the audience could enter the works through multiple points of entry, whether through the imagery or the stories.

Magazine 15. Photo: Zeynep Fırat. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Every project has its own needs, and sometimes fiction becomes the most effective way to mediate the artworks. It allows for a different kind of accessibility, one that is not prescriptive but evocative, inviting viewers to engage with the works intuitively rather than being guided by predefined interpretations. By integrating experimental writing into my curatorial practice, I aim to create exhibitions that unfold like narratives, where artworks, texts, and audiences become part of an ongoing dialogue rather than a fixed reading.

Your residency at Tarabya Cultural Academy and your focus on nightlife studies suggest a deep engagement with urban cultural dynamics. How have these experiences influenced your curatorial approach, especially in terms of addressing social resistance and community interaction?

During my residency at Tarabya Cultural Academy from February to May 2024, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Yelta Köm on an in-depth exploration of nightlife as a form of resistance. The residency provided us with the time and space to deepen our research, allowing us to examine how nightlife functions as a site of social agency, collective expression, and alternative forms of community-building. This research culminated in a substantial piece published in CTM Magazine, followed by further writing for the online platform Manifold, where we expanded on themes of urban dynamics, queer spaces, and sonic resistance.

Beyond research and writing, our engagement extended into practice. As part of Sommerfest, we collaborated with the initiative Queerwaves to organize Sound Kitchen, a one-day event that transformed the former kitchen of the residency into an intimate and safe gathering space. Resident DJs from Queerwaves performed throughout the event, while video works by Yelta added a visual dimension to the experience. The project was not just an event; it was an experiment in creating temporary, self-organized spaces where sound, bodies, and shared experiences could produce moments of resistance and belonging.

Sound Kitchen, Tarabya Cultural Academy. Courtesy of the artists. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

This experience reaffirmed my belief in curating as an active, community-engaged practice rather than a static, exhibition-driven one. My curatorial approach is shaped by the communities I am part of and the social and cultural contexts I navigate. I see exhibitions and public programs as platforms that can foster interaction, open up conversations, and create new forms of solidarity. The research on nightlife further sharpened my interest in how curating can engage with ephemeral, performative, and social experiences—especially those that challenge dominant narratives and propose alternative ways of being together in urban space.

all familiar, all foreign: Yelta Köm, installation view. Courtesy of Versus Art Project. © All rights belong to their respective owners. No copyright infringement intended.

As you think about future projects, what unexplored themes or collaborations are you excited to explore? How do these prospects align with your ongoing curatorial aspirations?

I’m currently working on a group exhibition that delves into the politics of collection-making and the evolving role of institutions in shaping communities. This project raises critical questions about how collections are formed, whose narratives they privilege, and how institutions can move beyond mere preservation to actively foster care—for both the artworks they house and the communities they engage with. I’m particularly interested in rethinking institutional responsibilities: Can a collection embody care? How can museums and archives become more responsive to the needs of their surroundings? What might the future of collections look like in an era where ideas of access, restitution, and collective authorship are being radically reexamined?

Beyond this project, I’m excited to further explore curatorial methodologies that center speculative thinking, queer and feminist perspectives, and alternative systems of knowledge production. I’m drawn to collaborations that challenge institutional conventions—whether through reimagining exhibition spaces, integrating experimental writing, or working with artists who explore social resistance and communal forms of existence. I’m aiming to work on projects that become active spaces of inquiry, dialogue, and transformation.

The impact of audience reactions and critiques can significantly shape the evolution of curatorial practice. Could you share how interactions from past exhibitions have influenced your approach to upcoming curatorial endeavors?

Exhibitions are not fixed statements but evolving conversations, shaped by the ways people engage with them. The moments when visitors challenge or reinterpret an exhibition are valuable, as they push me to refine my approach and think more critically about accessibility, context, and the narratives being constructed. The range of responses reinforced my belief in the necessity of speculative approaches to curating—ones that do not seek to provide definitive answers but rather create space for dialogue and contradiction. It also encouraged me to think more deeply about how institutional narratives shape public perceptions of history and heritage.

For instance, at Sound Kitchen, the event we organized at Tarabya Cultural Academy with Queerwaves, the audience’s engagement with the space—how they moved through it, interacted with the sound, and formed temporary communities—underlines the importance of spatial design and sensory experience in curatorial projects. It made me more aware of how an exhibition or event can function as an embodied experience. Moving forward, I want to continue incorporating opportunities for open-ended audience participation, whether through speculative fiction, interactive elements, or alternative spatial strategies.