Erotic Thrill

Basic Instinct doesn’t take you to conclusive answers. It dares you to wonder about your identity and your inner impulses. It’s the ambiguity of the movie that draws you to the screen. It’s an enigma of eroticism, violence, and temptation that will make you fall into a deep state of hypnosis.

Michael Douglas and Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, photography by Snap/Rex Features

Picture sex, high tension, and the thriller genre. Hollywood swamped us with many examples throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Other than Fatal Attraction, Sliver, Disclosure, and Unfaithful, we have many other movies that almost convinced us that sex and murder had to go hand in hand, mandatorily. But none of them quite went and will go down in history as an unremarkable masterpiece—as I’m pretty sure that most of you never even heard of these titles in the first place.

But there is one that, rest assured, if you named it to your parents they pretty much would all have the same reaction: “Oh, I know that one,” with a hint of a guilty, naughty smile on their faces. If we had to summarize the erotic-drama-thriller genre of the 1990s and 2000s, we’d have no other choice than to speak two simple yet magic words: Basic Instinct.

Born from the genius of Paul Verhoeven, it literally takes two minutes for us to get an idea of the general atmosphere. Introduced by the mellow musical swell of Jerry Goldsmith’s expertise, the first scene tells us all we need to know.

Coming down from a ceiling mirror, the framing focuses on two human bodies love-twisting one with the other. Then, the camera takes us to her. She’s wriggling over him. We can’t quite recognize her, as the blonde flowing hair is covering her face. She grabs a white rolled-up silk scarf and ties his hands to the headboard. She keeps on passionately moving over him until, from underneath the bed sheet, she pulls out an ice pick and ferociously stabs him over and over again. In a matter of minutes, we realize it’s about power. Manipulation. Sexual pleasure. Control.

Performance.

If by any chance you happened to have another example in mind about a performance of a female character as sensual as this, please come forward.

Sharon Stone is undoubtedly the personification of seductiveness and slyness assembled together. She’s smart and rich. She plays the part of a bisexual multimillionaire writer who graduated magna cum laude from Berkeley with a double major in literature and psychology. She got it all. Beauty, success, freedom.

For no hidden reasons, the female population sides with her character. Simply because she represents much more than a desirable and attractive 34-year-old Sharon Stone. She is the reflection of the power of true liberation for women. She’s the one who will get anything she wants when she wants it. She doesn’t need anybody to give her a compliment to know she’s beautiful. She doesn’t need a man to be and feel like a woman. She’s in total control of her life. She’s so in control that she can even think to commit a murder, write about it in a book, and still presume to get away with it. Probably, the lens provided by Verhoeven is not exactly feasible to reach in real life, as it involves quite a high stack of dead bodies. But still, she really represented the hope to be the dream figure for all women of the 1990s.

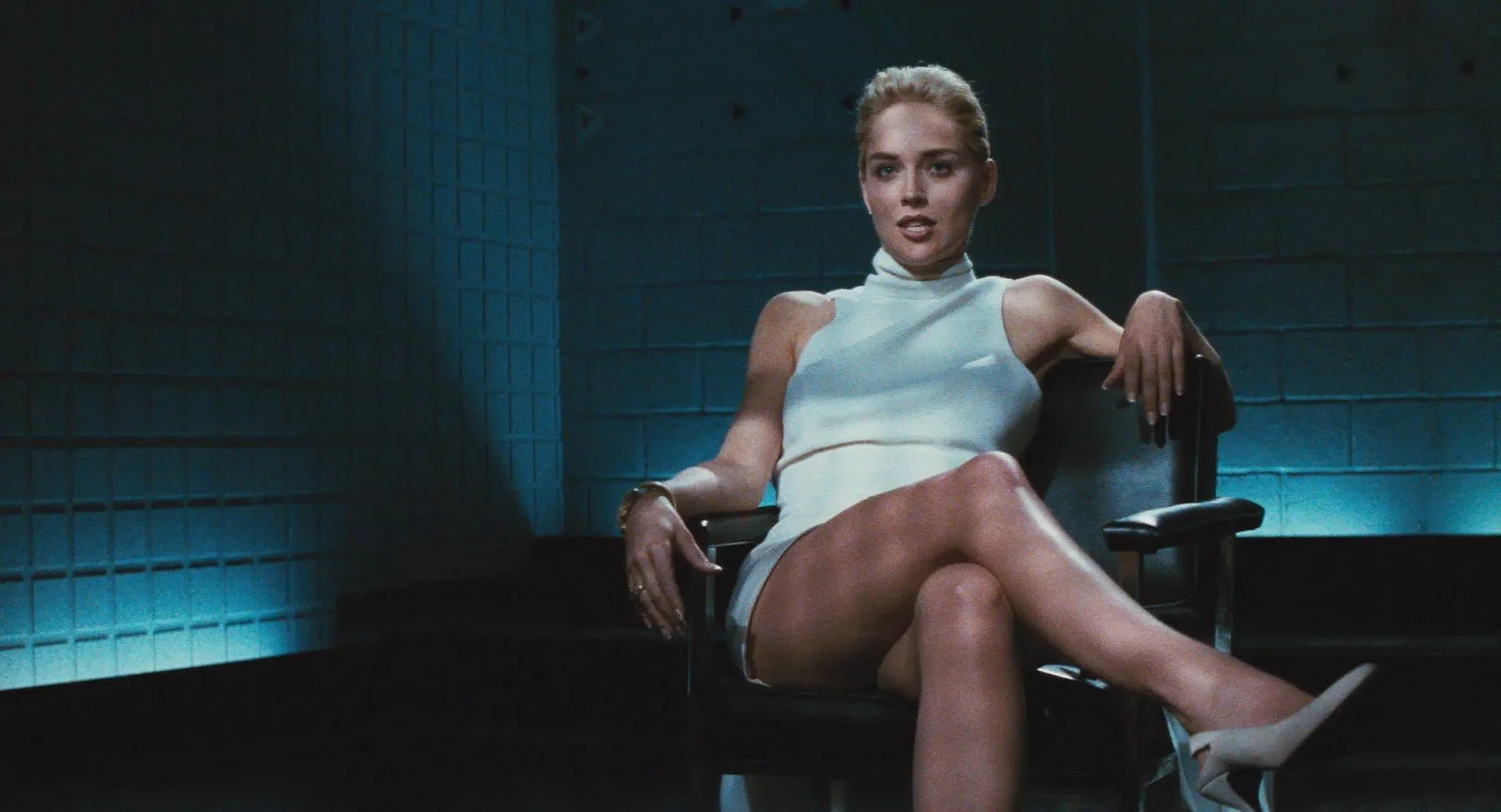

Sharon Stone in the interrogation scene, by Rialto Pictures

On the other hand, we have the real protagonist of this story: Michael Douglas.

He’s quite the puzzle to assemble. San Francisco police detective, recently divorced, and recently detoxicated from booze and coke.

He was involved in an accidental shooting that put him under Internal Affairs investigation—a situation that requires frequent sessions with Dr. Beth Garner (Jeanne Tripplehorn), with whom he’s frequently slept.

He’s the prototype of the on-the-edge/about-to-relapse cop, torn between pleasure and duty. He is in a bind and therefore, he plays the perfect pawn in Sharon Stone’s meticulous chessboard strategy. From representing the only weapon able to bring her to justice, he turns into the strongest defense she could have ever asked for.

Michael Douglas and Sharon Stone, courtesy of Everett Collection

Controversy and Provocative Content.

Director Paul Verhoeven's noir mystery faced outrage and attention for the movie’s graphic content, as well as for its underlying context.

A ferocious wave of protests came from the LGBTQ communities, who felt offended by the portrayal of bisexuality. How could you not be angry at the obvious association of being lesbian with inevitable violent psychosis?

Sharon Stone and Jeanne Tripplehorn were not only portrayed as pathological liars but violent and unstable as well.

But this is not the only point that made people turn up their noses. Other than the onscreen rape of Beth—almost normalized in the frame of the overall panorama—many other complaints stood at the heart of the protests.

The movie’s screenwriter—Joe Eszterhas, whose work is shockingly misogynistic even by Hollywood standards—made a career out of screenplays that used the torture of women and brutal sexual violence as its favorite subjects.

If we talk about controversies and scandals related to the movie, it’s mandatory to include the famous interrogation scene as well. Sharon Stone is surrounded by male detectives who bury her in questions. She’s not afraid of them, though, and in fact, she gets out of the situation on top. By using mental manipulation and sexual appeal, she puts the male figures on their knees. She directly challenges the attractive cop Michael Douglas, calling him out on his marriage and cocaine use. She uses the power of her stare while crossing and uncrossing her legs revealing the complete lack of underwear underneath. This is way more than what the simple scene may suggest. It’s not only about the scandal of extreme nudity used to get the attention of the audience; what lies underneath is a precise preconceived idea of what human genres stand for. Men are dirty. Easily distractable. They might have all the interests of life in mind, but, in front of the “forbidden fruit”, they demonstrate a total lack of objectivity and rationality. They are described as animals, drawn to the pleasure of human flesh.

Women are the object of men’s desires. They are the awards to win. They are depicted as mere material elements needed to satisfy dreams and fantasies. In fact, Sharon Stone, knowing the ugly reality of things, uses that very same principle to get what she wants. And in doing so, she shows the audience that women are smarter than men. As opposed to them, women can think straight and look at the long run.

The Thrill.

It’s not exactly clear whether our attention should be focused on the sensual part of the movie, or on the winding plot coming out of it. I’m not even sure viewers are there for the story itself. There are movies judged on the coherency, veracity, and smoothness of the events. Others are labeled for the atmosphere or mood they convey. And then, there are those that fall right into the middle. Basic Instinct is a masterpiece, not because of the construction of the story—as it would be kind of unrealistic to see certain things happening in real life, even if we can never really know—neither because of its sensuality alone. Paul Verhoeven developed an opera that was groundbreaking. It was revolutionary because it really understood the power that sex, drama, and violence held over people. Despite being a clear over-exaggeration of human society of the 1990s, the movie built a perfect formula that masterfully balanced several elements altogether: murder, mystery, love, tricks, power, control, and manipulation. They did this while being able to maintain constant tension and induce an internal conflict in the audience throughout the entire movie. We are not sure if we side with Sharon Stone or Michael Douglas. It’s difficult to say if we want her and all women to succeed—even though we know she’s guilty as charged. Or if we are more pleased with the idea of justice prevailing over crime and all the ugly truths of the world. Or again, there are those who are not rooting for any of these two options. These are those people who look at the movie as a potential love story between good and evil. This third option allows us to find a compromise and live happily with ourselves without the fear of feeling guilty.

Therefore, don’t judge the movie based on the cinematographic perfection itself—especially because if you did, you’d end up being disappointed with every single movie ever made. Don’t judge it either based on the controversies hurled at it over time. Consider the novelty. The courage to do certain things at that time. Think of the adrenaline rising up as the frame keeps on piling up. Examine the sensuality and the beauty of sex. Keep in mind what are the reasons that make us stare at the screen for 2 hours and 8 minutes. Is it the pleasure of flesh? Is it the feeling of getting away with something knowing you’re guilty? Is it the unpredictability of events changing directions out of the blue? For all these and many other reasons, Basic Instinct remains a one-of-a-kind.