Edward Hopper, Art & Cinema

The expressive power of Hopper's works made them a valuable reservoir for cinema, particularly for the films of Alfred Hitchcock and Wim Wenders.

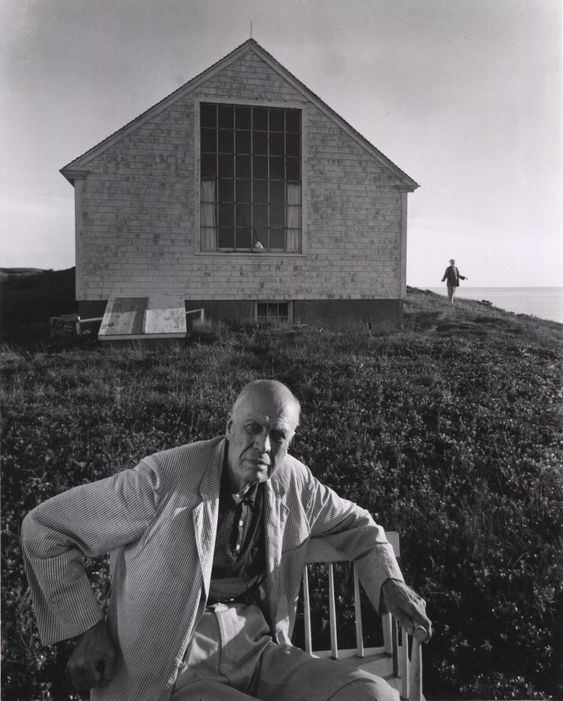

Edward Hopper. Via “Sotheby’s,” 2018.

Edward Hopper was one of the most sensitive interpreters of American Realism, an artistic current of the twentieth century that aimed to tell the story of the American way of life at the turn of the two wars. Hopper unfilteredly recounts the U.S. of the Great Depression, investigating its most everyday and seemingly mundane aspects, to the point that his paintings appear as archetypal images, timeless icons of American modernity in the provinces and metropolises, which led critic Lloyd Goodrich in a 1927 article to claim that "it is difficult to find a painter who, in his pictures, expresses America better than Hopper." The power of Hopper's images—no matter whether it is the interior of a cramped New York diner or a house on a sunny prairie in the American countryside—lies in the atmosphere of apparent calm and stillness that actually communicates a sense of unnerving anticipation, as if his characters are waiting for something or someone that may never even arrive. The expressive power of Hopper's imagery—soaked in silences, waiting, introspection, and incommunicability—has made his art a valuable reservoir for cinema, another icon of contemporaneity. Hopper himself, a great fan of cinema, was inspired by it, as is evident in the cinematic slant given to his works in a constant relationship characterized by mutual influences. Numerous filmmakers—from Michelangelo Antonioni to Dario Argento, via Ridley Scott and David Lynch—have been affected by the fascination exerted by Hopper's atmospheres. But among the many who have drawn heavily on the American painter's aesthetic, the master of the thrill ride, Alfred Hitchcock, and German director Wim Wenders, stand out in particular.

The All-Seeing Eye in Alfred Hitchcock and Edward Hopper

Heavily influenced by Hopper's art, the English master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, shares with the American painter the same voyeuristic and omniscient eye, which goes so far as to strip away all privacy from the existence of the people portrayed, immortalized in everyday actions inside their homes, as happens in “Night Windows” (1928), Hopper's famous canvas where a woman, whose face we do not see, wearing a skimpy petticoat, leans forward unaware that she is being watched. Certainly, owing a debt to Hopperian aesthetics, is “Rear Window” (1954), a cult film by the thrill genius, centered on the figure of Jeff (James Stewart), a photojournalist momentarily confined to a wheelchair, who spends his convalescence spying on the lives of his neighbors from his windows, armed with a spyglass.

On the left, E. Hopper, “Night Windows,” 1928, MoMA, New York. On the right, scene from “Rear Window,” A. Hitchcock, 1954. Via “Frammenti Intervista,” 2022.

The filmic sequence showing the building shrouded in the darkness of night, lit only by the windows, small worlds in which fragments of life unfold, seems reminiscent of “House at Dusk” (1935), characterized by the simultaneous viewing of multiple windows on the top floor of a mansion at dusk, where the shots on the individual windows recall famous paintings by the painter, such as “Room in New York” (1932), in which a man reads the newspaper while a woman sits listlessly at the piano, each immersed in his or her own solitude.

Alfred Hitchcock. Via “Bored Panda,” 2021.

Just like the photojournalist in “Rear Window,” Hopper said he often observed the interiors of homes during his nocturnal walks, paying particular attention to the psychological aspects of couples' lives, and then drew inspiration for his works. Another major point of contact between Hitchcock's cinema and Hopper's art can be found in the focus on U.S. urban architecture, as is evident in the Bates Motel in the film “Psycho” (1960), home of Norman Bates—one of cinema's most famous psychopaths—an almost literal transcription of the canvas “House by the Railroad” (1925), a remote multi-story cottage in the American countryside.

On the left, E. Hopper, “House by the Railroad,” 1925, MoMA, New York. On the right, scene from the film “Psycho,” 1960. Via “Frammenti Intervista,” 2022.

Incommunicability and Loneliness in Hopper and Wim Wenders

An interpreter of the New German Cinema, a movement of renewal in German filmmaking at the turn of the 1960s and 1980s, Wim Wenders, who has always been an admirer of American culture, has repeatedly cited Edward Hopper as a primary source of inspiration for the imagery of his cinema, characterized by seemingly infinite spaces and lonely characters in search of themselves. A direct homage to Hopper's best-known work, “Nighthawks” (1942), can be found in “The End of Violence” (1997), where the glassed-in nightclub, where the famous insomniacs meet, is carefully recreated on the set for one of the film's sequences.

On top, “Nighthawks,” E. Hopper, 1942, Art Institute of Chicago. On the bottom, scene of the film “The End of Violence,” W. Wenders, 1997. Via “Frammenti Intervista,” 2022.

Hopper's influence on Wenders's cinema is particularly evident in the films centered on travel, his atypical, slow-moving road movies, where the American landscape flows by through the windows of a speeding automobile, as is the case in “The American Friend” (1976) and “Paris, Texas” (1984). In fact, the U.S. of “Paris, Texas” is studded with billboards, gas pumps in the middle of nowhere, impersonal motels, and endless road trips, all recurring elements in Hopper's art—just think of the gas station in “Gas” (1940), or the spacious interior of the “Western Hotel” (1957).

Wim Wenders. Via “Indie Cinema”.

Wenders' films seem almost to bring Hopper's characters to life, bringing their story to fruition beyond the mere snapshot reproduced in the painting. This operation was, moreover, effectively carried out by the German filmmaker in the 3D short film “Two or Three Things I Know About Edward Hopper,” made on the occasion of the exhibition dedicated to the painter by the Fondation Beyeler in Basel in early 2020.

On the left, “Gas”, 1940, MoMa, New York. On the right, “Two or Three Things I Know About Edward Hopper”, 2020. Via “Frammenti Intervista”, 2022.

In the short film, Wenders animates some of the painter's famous canvases, imagining the stories and relationships between the enigmatic characters portrayed and thus answering the fateful question that anyone might ask in front of a Hopper painting, 'And then what will happen?